What is culture?

Culture is a complex, abstract framework manifested through various societal elements like arts, law, and daily interactions. It’s not just about individual components like price mechanisms or entertainment but serves as a social mechanism that transforms self-interest into cohesive group behavior, ensuring societal survival. Using fire ants as an analogy, the article illustrates how individual actions collectively form a societal structure to withstand chaos and maintain stability.

To say that we cannot see culture may seem absurd. When we move between two societies, especially two contrasting ones, we can practically feel it on our skin. The way a city looks, its billboards, entertainment, and language, along with the subtleties of how people interact, all contribute to this.

A well-known difference here is when it comes to buying souvenirs in local markets. In a Western context, the price is set, and the business of haggling is handed over to the free market mechanism. If the price is too low, supply cannot keep up and if the price is too high demand dwindles. By contrast, other cultures leave it to the individual for an even freer market. Displayed prices are mere suggestions, and a range of haggling tactics are employed, allowing the seller to determine the real price the buyer is willing to pay and for the buyer to discover the lowest amount the seller would accept.

This is undoubtedly a cultural difference. However, reducing culture to a price discovery mechanism is perhaps a bit simplistic, as is reducing it to any other single element like dance, art, language, or a legal framework. It is more palatable to say that the arts are indeed culture, yet even this feels inadequate. And at the same time we’re left wondering ‘what more can it be’.

What is culture?

Everything mentioned above, and any physical evidence of culture, can be seen as manifestations of culture. These are the artifacts in the real world that allow us, as people in a three-dimensional world, to interact with the abstract framework of culture.

To think about it, lets take a step back and ask ourselves why we have culture. In evolutionary terms, ‘culture’ carries the same contradiction as the human brain. Evolution is a very economical process — it optimises for survival in scarce conditions. And yet the human brain contributes to risk in child birth and uses a lot of energy. Nevertheless, it has enabled humans to thrive beyond the top of the food chain.

Culture is a similarly expensive feature. Consider the amount of resource, especially at a social level, that is poured into bringing culture to life. How much time and energy is spent on entertainment and the arts. Just ‘enjoying ourselves’. But, as above, culture is not just the arts. Culture’s function becomes clearer when we consider other areas, like law, which consumes vast amounts of individual and societal resources. The law for instance employs an army of people dedicated to evolving, interpreting, applying and enforcing the law. They range from highly specialised legal scholars who think about what it means to be just in a specific and complex context, to the beat cop who understands the community, applying and enforcing law for social stability.

I trust that in moving from entertainment to law the function of culture becomes clear. More than just a byproduct, it is the backbone of society. Law might feel arbitrarily stacked against us. And while there are definitely cases where the technicalities of law did not result in justice, law in principle is simply a codification of a series of behaviours that can be understood as ‘if we behave in this way, our society will survive’. And because we depend heavily on our societies, this translates into survival at the individual level.

Key to note is that individual survival is not the focus of any evolutionary process. The survival of the specimen is only a priority in as much as it supports the survival of the species. We have not evolved beyond our physical weaknesses, but we’ve evolved far enough to get enough people to productive age to ensure the survival of the species. Similarly, culture promotes the individual in as much as it ensures societal survival. ‘My freedom to swing my fist ends where your face starts’ is as close as we can get to total individualism. And in terms of sacrificing the individual for the group, well history is littered with examples of ‘making an example’ out of individual criminals to ensure the stability of society.

An analogy

So far we’ve looked at why we have culture. But our core question remains unanswered. How can we think about a ‘what’? Oten the best way to understand a highly abstract concept like culture is at the hand of an analogy.

Top that end, bugs are useful when it comes to explaining cultural behaviour. We can be mezsmirised by the detail and the noise of human life but when we look at bugs, we are blind to the intricacies of day to day bug life. This makes it easier to focus on the macro picture. Fire ants are particularly useful when it comes to explaining culture.

Fire ants

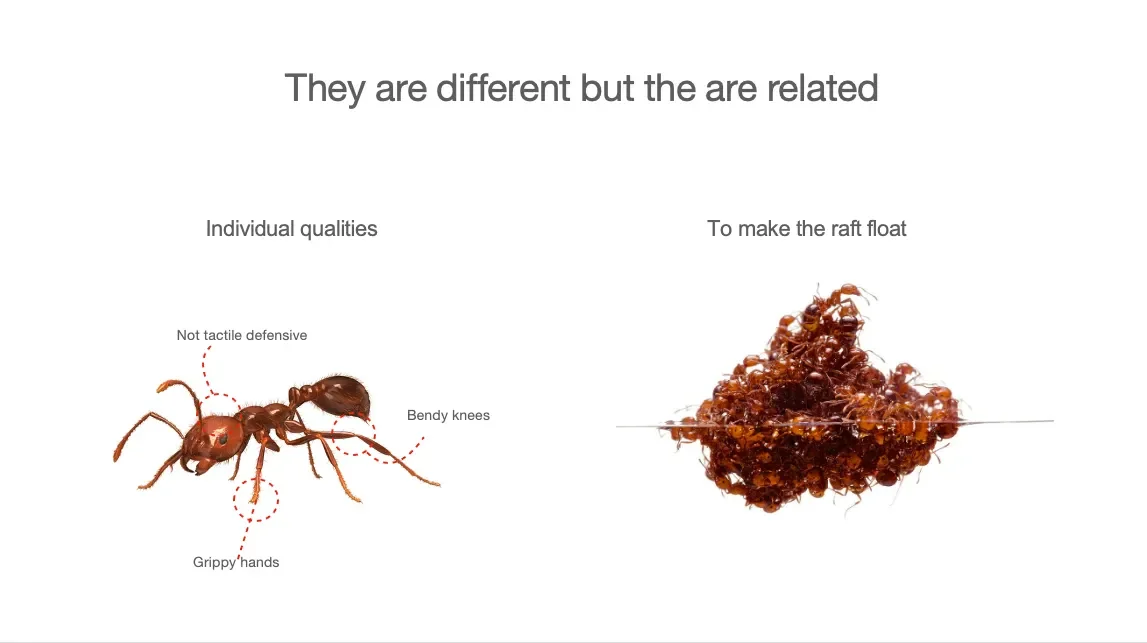

When water threatens a colony, Fire Ants starting forming buoyant clumps of ants capable of ‘sailing’ whatever flood or water mass came their way. But these clumps or not just ants randomly holding on to each other, hoping for some collective buoyancy and the off chance that most will remain above the waterline. Instead, it’s a carefully orchestrated collective movement that traps air, defends the most important colony members and even rotate individuals through the raft to make sure no one stays under water for too long.

This is a useful and tangible example, but can we make it more practical? The ants are obviously the individual members of society and the raft is our culture. And like our culture, we don’t actually see the raft, we see hundreds of ants, and yet, when the position themselves just right and find themselves on water, we can see that it’s a raft made of ants.

The connection points between the ants and their raft or ‘culture’ is however visible. It’s not a physical connection, that is to say, you follow the connection and you find the raft. Instead it’s in their behaviour and the physical ability to engage in this behaviour. Their legs can bend just the right way, their grip allows for them to hold on to each other and their bodies provide just the right places for the other ants to grab. It’s as if they were made for this.

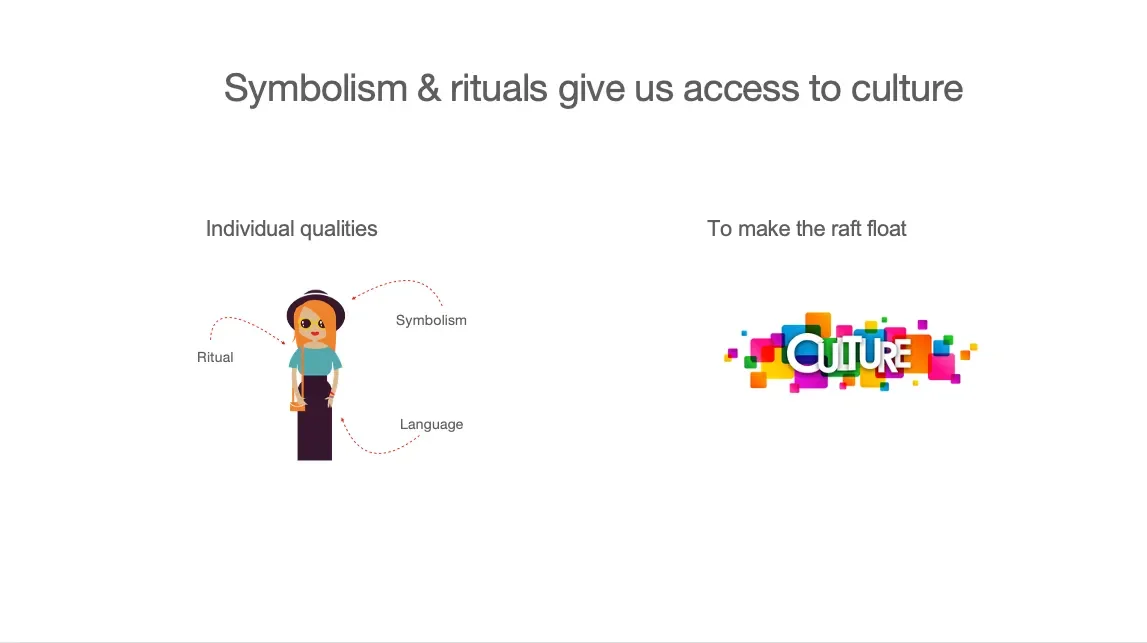

Their propensity to engage in this behaviour when the flood waters rise and their physical ability to do so is musch the same as our ability to recognise a social situation, communicate, engage in group behaviour and to follow rules.

In the same way that ants physically reach out to hold onto each other to prevent flood waters from sweeping the individuals away, we communicate, share information and engage in rituals in order to keep our proverbial flood waters at bay.

The obvious question then: what is our version of a flood? This is worth a discussion on its own but we can think of it as the archetypal form of chaos. It’s the reality articulated by unbridled self interest, no way of engaging with or defending against the world around us and no real way of leveraging our natural human qualities to ensure the survival of our immediate or broader social group.

Understanding culture

We can now start to understand why common elements are found in culture which all manifests in different ways. Culture seems to be a relatively rigid framework that at the same time can be adapted to suit many environments. In our example, the abstract idea of an ant raft can on many surfaces with varying amounts of ants for different durations. But all these rafts would require some basic functions (rotating ants through the raft, trapping air and so on). Similarly, human culture can be serve its function in many environments, for populations of various sizes and ethnic backgrounds for as long as it meets certain requirements — allows for communication, value exchange and so on.

A specific culture can be described in terms of the actual rituals and artifacts we see. But culture in principle, the abstract idea, is a Darwinian survival mechanism that allows a group of humans to deal with their environment and each other.